PREFACE by Jason Christopher Hackwith

ON POETRY

Poetry is a bright light, illuminating the farthest, most desolate reaches of the soul. Poetry is darker than midnight; a useful mask, opaque and forbidding. I love the dichotomy of poetry, the paradox of it: day and night and shades of twilight rolled up into one. It’s easy to hide the heart behind colorful metaphors and well-turned phrases—even as you disclose the deepest depths of your heart to the world.

Poetry has been such a hiding place for me in the darkest times of my life, and the brightest. The strange pulling of a blank page yearning to be filled, the catharsis of the release of emotions; the indescribable feeling when you read and reread the finished poem and feel the truth captured there, fluttering like a caged bird. It always seems to me as if I am a minor part of the process. I’m just moving the pen.

The transitory nature of poetry is fascinating to me. A poem may glow eternal within the heart of the writer, or it may briefly illuminate a single moment: BANG! and a flash quickly fading to darkness. You never know which.

Words written on a page are never as lasting as words written on a heart. Unless a true connection is formed, a poem is a mist—disappearing as quickly as it appears. At best, understanding someone else’s poetry is an educated guess. At worst, it’s a reckless shot in the dark. Sometimes, however, the heart wins through, the metaphors burst into clarity, and the reader and poet share a moment of true understanding. More than anything else, that is what I am attempting to do here.

Of course, it’s never that easy. Some of the most seemingly revealing poems contain layers upon layers of hidden meaning; some of the most seemingly obscure poems can actually be the most revealing. The most immediate and obvious interpretation can often be incorrect—at least as far as the poet’s original intentions for the poem are concerned. It’s an interesting paradox. The poet desperately seeks understanding, but the very nature of the medium promotes obfuscation. Something tells me that dear old Pascal had it right:

“Poète et non honnête homme. (A poet and not an honest man.)”

The truth is, poetry is always a co-creative process. The poet can never truly know exactly what strange new creations his work will generate within another’s heart and mind—nor should we fall to the conceit that we ever fully will. We simply do not have the frame of reference for complete understanding of any other human being.

The wonderful thing about poetry, however, is that complete understanding is not necessary. All the denotations and connotations of the reader’s mind mingle with the poet’s, and something new is born.

I’ve been writing and reading poetry long enough to understand that I really have very little control over this new thing we are creating together. It’s a fascinating thought, and a humbling one: this book is just as much about what you bring to it as the words I have written down. Your triumphs and failures, loves and losses are the colors that fill in my black & white drawings. Rather than be intimidated by this fact, I choose to acknowledge and embrace it. To tell the truth, more than once I’ve written something and stared at it long afterwards, slightly disturbed; wondering just what strange corner of my mind it came from. Some of my poems are that way: looking back even I can no longer tell you exactly what I was thinking when I wrote them. The moment came and went; the words remain.

On the other hand, some poems have become so much a part of me that I just can’t imagine life without them. Brief moments of truth, epiphanies captured, even painful memories of love lost are precious to me.

They are pictures in an album, snapshots of my life and loved ones. I take them out from time to time and nod, smile, wipe away a few tears, and consider where I have been.

PER TENEBRAS, LUX

It has been twenty-five years since I first came to the Lewis-Clark Valley near the close of the summer of 2000. The year that followed was one of the darkest times of my life. I would see darker ones, but in 2001 I saw my faith tested, my heart broken, my illusions shattered by the horror of 9-11, and the pieces of my life slowly reassembled.

When I graduated from Coeur d’Alene High School in 1996 and traveled 500 miles away to Northwest Christian University in Eugene, Oregon, I felt almost as though a bell resounded and the heavens opened up: it was that clear to me that I was exactly where I was supposed to be. When that time in my life came to a close in 2000, the bell remained frustratingly silent.

I honestly had no idea what I was to do next. I looked for a job in Eugene, but it seemed as if every door was closed to me. Frustrated beyond words, I became terribly cynical and closed even to the people I loved the most. Finally, feeling like a failure, I moved to my parents’ house in the Lewis-Clark Valley to regroup. As the days grew shorter and the nights grew longer, I felt as if my own light was slipping away. I was disillusioned, disheartened, severely depressed—and completely broke.

I attended my parents’ church and found a job fairly quickly, but “real life” after college was not at all what I had expected and I decided I didn’t really care for it. I went through the motions of the day as best I could, and came home to my basement room to stare into nothing. I felt as though I had somehow done something terribly wrong without meaning to. I thought that I had somehow strayed from the path I was supposed to be walking, and God had abandoned me in disgust.

I missed my friends in Eugene, and felt completely severed from the life I had come to know over the past four years. My family was loving and supportive as always—but to me everything seemed dark and hopeless. God, who has always been there for me in the darkest times of my life, seemed to have suddenly become an enormous deaf ear.

I know now that what I was walking through for the first of many times in my life is what Juan de la Cruz called la Noche Oscura del alma—“the Dark Night of the soul.” There comes a time in every person’s life when he or she faces an overwhelming, almost unbearable emptiness. God seems far away, prayers seem to bounce off the ceiling, and all the loving support and kind advice of family & friends just rattles shrilly in your ears.

A great disconnection forms between yourself, the life you are enduring, and what you believe. The silence is deafening. This is the legacy of Job, the lamentation of Jeremiah, the doubt of Peter, the cross of Christ: the continuing fellowship of sufferings that belongs to every believer. No matter how strong your faith is, when the dark night of the soul comes, the world as you know it is at an end. You will never be the same.

The Valley became such a test for me; one I failed. Spectacularly.

Instead of being immediately driven into the loving arms of my Father where I could patiently wait in faith for clearer skies, I wallowed in self-pity and engaged in self-destructive behavior. Instead of finding the strength to endure life’s changes and challenges with patience, I fell into one of the greatest depressions I have ever known. Thinking myself so wise, I proved the fool.

When my first Dark Night came, I was completely unprepared. It would take unexpected friendship, love, and loss to finally disturb me from my navel gazing. It would take the unparalleled horror of September 11, 2001—and the shift in my worldview that swiftly followed—to clear my gaze to the point where I could stand, blinking through my selfish tears, and fall back into the arms of Grace. For a little while.

Twenty-five years later, I stand in the midst of another series of overwhelming tests: terribly dark nights in relentless succession punctuated by moments of clarity that are almost painful in themselves. I am a survivor of three heart attacks, lengthy unemployment, poverty, a failed marriage, congestive heart failure, and many difficulties. I have never felt more blessed. One of the greatest blessings is my beautiful Lindsay, this amazing lady who has quietly yet utterly conquered this healing heart. Along with her, I am surrounded by the greatest of saints: friends and family who have been there for me in good times and bad. God has been faithful in providing our needs. I am more conscious of my own mortality than I ever have been, and yet I have never felt so terribly alive.

I face an uncertain future, but I am learning to be more present than ever. “Just take care of today,” one of my friends is often heard to say—and I am learning at the age of forty-six to do just that. God is teaching me to trust.

ILLUSTRATION as EXPLANATION

I’ve been a graphic artist and designer for years, but for most of them I always felt like I had to apologize when people asked me to do an illustration. I would usually do my best to come up with some reason they should go with someone else. “I’m not really an illustrator,” I would say. “I’m really just a designer and typographer.”

If asked to explain further I would probably stammer and say something like, “I’m not really an illustrator because.. well, because I lack the bulk of formal illustrative training, and because I’ve known some truly excellent illustrators and because... I don’t really feel like I measure up.”

Truthfully, however, I’m far too often guilty of ‘setting the bar’ too high for myself to reach—a trait common to perfectionists that, at its core, is really a form of self-abuse.

I’m working on that.

A very kind friend took me aside one day after overhearing me tell someone that I wasn’t an illustrator, and in the most blunt terms possible told me that wasn’t really an honest thing to say.

“Don’t you want to be an illustrator?” he asked me, looking at me intently.

“Well, yes,” I replied. “I just don’t think that I’m very good compared to some of the amazing artists I know.”

“Jason,” he replied with a slight smile, “is a believer ‘not really a Christian’ just because he knows some amazing Christians and doesn’t feel he measures up to them? What would you tell a believer who always felt like he was never good enough to be one?”

I got his point almost immediately, but it’s taken me years to start referring to myself as an illustrator. I still feel like I haven’t really earned the title, but then again, that’s how I feel about being a Christian. I have a very wise friend.

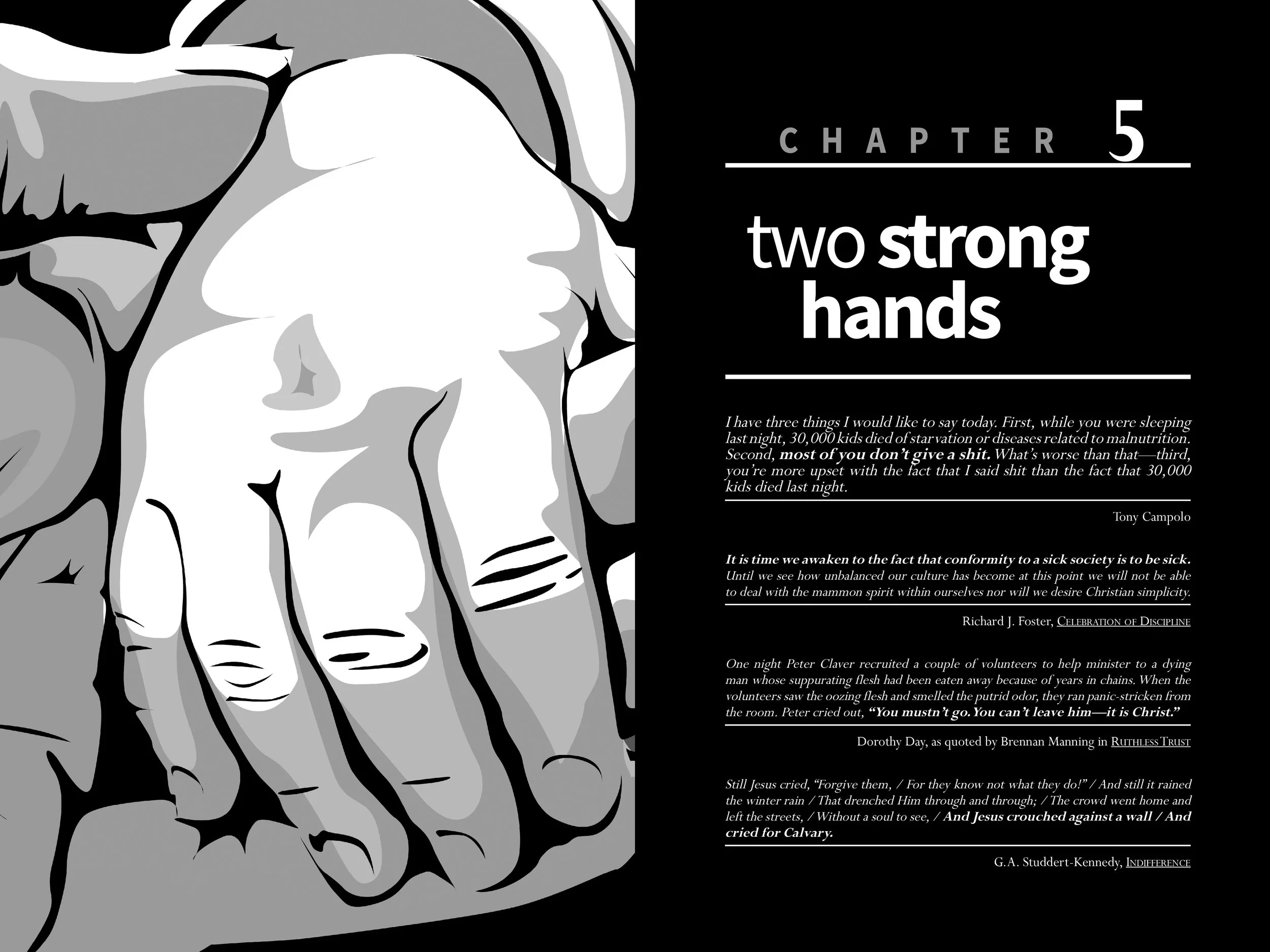

The images that I’ve included in this work are for the most part direct visual associations I have had while writing the accompanying poem or lyric. Some arrived with the poem as one overwhelming package, some came years later. Some poems inspired illustration, some images inspired poetry.

I have not illustrated every poem. Beyond the simple fact of the vast scope of work that this would quickly become, I try to write poetry that forms its own illustrations and visions within the reader’s mind.

However, some images are so powerfully attached to the poem I couldn’t help but include them. To tell the truth, some images are very hard to endure. The terrible vision that inspired “Not A Sparrow Falls” (page 37), for example, was practically seared into my mind with a great deal of horror and pain. I see it involuntarily every time I re-read the poem. After a lot of careful consideration and prayer, I have decided to include it here. I am certain there will be readers who wish they could forget as well.

TYPOGRAPHY as EXCLAMATION

Few elements of design bring me such pleasure as typography. I am most certainly a design geek when it comes to many things, but the art and science of typography never fails to bring me joy. There’s just something about the careful arrangement involved that reminds me of crafting music. When you get it right, the letters seem to flow together effortlessly and practically sing.

I feel as if I’ve been privileged to have been given a glimpse of the universe of music that lies just beneath these black and white letters. Some works quite simply explode with an impulse to create typographic exclamations. I’ve included these where it seemed appropriate.

NIL NISI CRUCE

My maternal grandmother, Doris Harms Pederson, was a brilliant but largely unknown poet. She once wrote of her poetry that she “kept words as pets.” I love that metaphor—it does much to reveal her poet’s heart and wit. My own writing, however, is often considerably less domesticated.

One of the common reactions that I receive from people when they read my writing is that some of it seems almost too brutally honest to take. I think my poetry in particular often ends up that way simply because life is that way: it is too awful, too terrible, too wonderful to face directly.

We cover up life’s naked parts. We find ourselves ashamed to look upon life’s ugliness—or unable to face its beauty—and so we build masks upon masks until we don’t even know ourselves. It’s easier by far to gloss over the bumps and bruises, to pretend that everything is okay; that Christians never face cynicism, doubt, poverty, or sorrow; that life just gets easier all the time—“and now, I am happy all the day.”

I have found that part of the catharsis in crafting truly honest poetry, music, prose and illustrations involves taking such things too awful, too terrible, too beautiful to accept within ourselves, and placing them safely on a sheet or two of clean, white paper. The worst within us loses power, the best seems somehow more approachable when we can face it outside ourselves.

This work is not exhaustive. After much introspection and prayer, I’ve chosen to include some very personal and painful works that I honestly thought would never see the light of day. For some, it does not feel like the right time.

In truth, this creation has been reworked many times, and exists now in a form that bears very little resemblance to its genesis.

To be honest, simply deciding to publish this work been a trial in itself. The overwhelming question I have struggled with has been, will that real, honest connection be made? Will there really be understanding? Will this matter to anyone other than myself? I can’t help but believe that these words and images are not just for me, and so I choose now to step out in faith, publish the work, and watch to see what God will do.

So, my dear reader, I have only one request for you: If something here touches you in some way, however miniscule, good or bad, will you please take a moment to let me know?

Love it or hate it, I sincerely treasure hearing from you. You can personally drop me a line or text at 208.298.9083, and/or get connected with our community of creatives.

VALLEYS FILL FIRST

As I’ve endured the best and worst of what life has brought to me, I think perhaps I’ve managed to learn a few things along the way. I’ve learned that I will face sorrow, pain and death throughout my life, but that God will never, ever leave me—even when He seems far away, He is closer than a breath. I have learned to remember in the dark what I have seen in the light.

I have known death and life. I have known joy, and have become very acquainted with her darker sister, sorrow. I have known betrayal and loss and grief so crushing it was all I could do to breathe. I’ve discovered the indescribable glory of truly loving a woman, and being loved in return, despite my many flaws. I have seen the face of Christ on the most rejected of persons and found Him waiting in the most unlikely of places. I have watched as my preconceptions, prejudices and ethnocentric fears have been stripped away one by one by terribly real encounters with terribly real people. I have dared to pray some dangerous prayers to a truly dangerous God—and lived to tell about them to anybody who would listen. God is so loving and so good, yet He is also dangerous because any real encounter with Him will leave us forever changed. I have so far left to go, but with humility, non sum qualis eram—”I am not what I once was.”

Through the darkest of nights and the most tender of sunrises, I know that I have only just begun to delve the depths of the “reckless, raging fury that they call the love of God” (Rich Mullins, The Love of God). Brennan Manning called it “a relentless tenderness.” Martin Buber spoke of being “endangered before God... engulfed in God’s abysses.” To George Croly it was the “flame.” To Edward Young, a “sacred shade and solitude.”

And what is the love of God to me? Shall I dare to name the ineffable? I must. The words pour out of me and I cannot stop them. They are water and fire and life and blood and power.

The love of God is a great and powerful River of life, filled not only with every tear that has ever been cried, but also His great, vast tears of infinite, ineffable compassion. I name it Beautiful. The river Beautiful is terrible in its awesome, relentless tenderness. It is indescribably, painfully, heart-stoppingly beautiful; a relentless, reckless, raging storm of love. It is so wide I can never cross over, so deep I could never touch the bottom. Inexorable and irresistable, the love of God upholds and uplifts every relationship and saturates every part of my life. The River is there in the darkness and in the light; in the joy and in the pain. I am carried along and lifted up, tossed about—and forever changed.

As I write this, I am only forty-five—and yet I feel that since I first came to the Lewis-Clark Valley, I have become an old soul. Surely, I have lived a hundred years in these past twenty-four. I’ve known poverty, and I have known plenty. I have known disease and I have known health, I have known betrayal and I have known real love, and while I would not begin to say that I have found the secret of trusting Him in all things, I am learning.

I am learning to breathe when all the lights go out and the world trembles.

I am learning to remember in the darkness what I have learned in the light.

I am learning that the greatest blessings are found in the strangest of places.

I am caught up in the reckless, raging love of the river Beautiful. I struggle and sink and come up gasping, renewed and refreshed and challenged and uplifted. “I ebb and flow within this tide / Yes, even in weakness, I abide.”

I have learned why we spend so much more of our lives in the Valleys than on the Mountain. And this, dear reader, more than anything else, this is what I want to share with you:

That’s where the River is; deep and wide.